Russian emigrants do not give up

Free Russia already exists

© Emiel Petrovitch

© Emiel Petrovitch

25 years ago, Putin was first elected president of Russia. A quarter of a century later, the country was occupied by a dictatorial and warlike regime, but a democratic Russia emerged in exile. Since the invasion of Ukraine, an estimated one million more Russians have left their country. MO* delves into yet another political emigration in Russian history.

This article was translated from Dutch by kompreno, which provides high-quality, distraction-free journalism in five languages. Partner of the European Press Prize, kompreno curates top stories from 30+ sources across 15 European countries. Join here to support independent journalism.

‘Like small, free America in Canada in The Handmaid's Tale’. This is how activist Asha Suvorova describes ‘her Russia’ in exile. All Russians who did not want to remain silent after the invasion of Ukraine were affected. Many went into exile. Some exiles continue to actively work for change in Russia, others support Ukraine, and still others want to contribute to their new country, or try to rebuild their destroyed communities there.

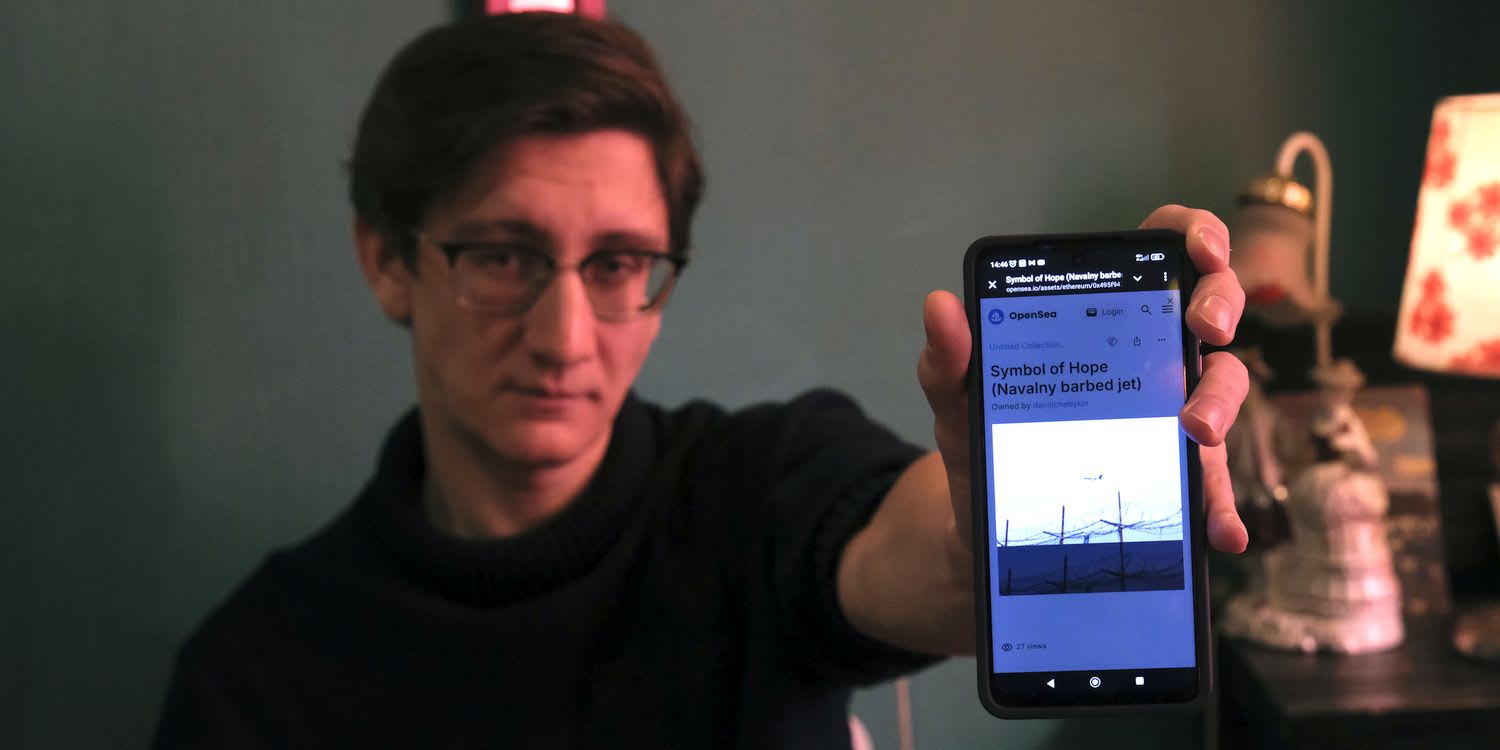

Many associates of assassinated opposition leader Alexei Navalny had fled before the invasion, as his organisations had been labelled "extremist". Daniel Chebykin, who trained election observers in Omsk and watched the poisoned Navalny take off for Berlin as recently as 2020, was fined a hefty 16,000 euros. After months of unsuccessful litigation against the fine, he fled to Armenia. That was three weeks before the invasion.

In St Petersburg, his colleague Daniil Ken was leader of a teachers’ union founded by Navalny. Today, from his small flat in Yerevan, he prepares broadcasts for Navalny's YouTube channel, broadcasts that reach millions of Russians. Yevgeny Zhukov was an election observer for Navalny's team. After the invasion, he helped thousands of Ukrainian refugees get free medicine in Tbilisi, Georgia. These are just a few examples.

On August 22, 2020, a plane takes off from Omsk bound for Berlin. On board: the poisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Daniel Chebykin shows the photo he took at the time.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Time to go

The exodus began immediately after the invasion. Tichon Dzhadko, editor-in-chief of TV Rain, Russia's largest independent TV channel, told his editors in Moscow: ‘It is time to go. Criticism of the army is punishable by prison terms of up to 15 years. From now on, journalism is a crime.’

Dzhadko initially thought the laws were just part of a new chapter and not the end. But then he received anonymous warnings about upcoming arrests of journalists. TV Rain's website was blocked, but the arrests never came. ‘To vote Draconian laws and then spread a few rumours is enough to drive us into exile’, says Dzhadko. He moved the entire editorial team to Riga, where ratings actually rose.

There were many chapters of repression, but the end was never written. ‘Look who is on the list’, TV Rain journalist Vladimir Romenskiy had laughingly said a few years earlier. The Justice Ministry had published a new list of ‘foreign agents’ and this time Romenskiy was on it. He had reported on the protests in Belarus in 2020. The repression there then led to a massive wave of emigration. Now Romenskiy is an emigrant himself. When Dzhadko addressed the editors, Romenskiy was on holiday in Georgia. And there he would build his new life.

Many Russians initially tried to protest against the invasion of Ukraine. Daniil Ken took to the streets but was arrested, his house searched and his passport taken away. Asha Suvorova even dared to hang the Ukrainian flag on her balcony. It did not last long. ‘My neighbours demanded that I remove the flag. I cannot live with such people.’ Stanislav Dmitryvsky, a Russian war crimes investigator, was the driving force behind the protest in Nizhny Novgorod. After two arrests for a Facebook post, he fled to Tbilisi to avoid a prison sentence.

But not everyone could turn their lives around. Dmitryvsky's colleague Igor Kalyapin, an icon of the Russian human rights movement, now lives in a remote village in Russia. ‘A human rights organisation should denounce war crimes’, says Dmitrivsky, ‘but in Russia you have to keep silent about the war.’ Igor chose to remain silent. ‘Igor has been a dissident since the Soviet Union, but this war broke him.’

Journalist Vladimir Romenskiy in front of a wall in Tbilisi: ‘Russian warship fuck off. Fuck Ruzzia.’

© Emiel Petrovitch

Kremlin follows everywhere

In an office in Tbilisi, a Georgian teacher teaches fugitive Russian activists and journalists. Asha Suvorova is one of them. ‘This is special’, she says after the lesson. ‘Georgians always had to learn Russian, now I teach their language to challenge the colonial Russian mentality.’ Suvorova works at Paper Kartuli, a new medium that brings stories about what Georgians and Russians share.

In turn, Yevgeny Zhukov puts himself at the service of Ukrainians. In Tbilisi, he founded Emigration for Action. In an old house, he stacks medicines for Ukrainian refugees. Outside, the white-blue-white flag of free Russia flies. ‘When we tell Ukrainians where we come from, most respond with: “Fortunately, there are also good people in Russia.”’

For these Russians, exile means rebuilding their lives, continuing to help others, but also dealing with the political repression that continues to haunt them. Because of the fine hanging over his head, Daniel Chebykin could not renew his passport. He was in Yerevan when the Russian authorities now also revoked his identity card, forcing him to seek asylum under the Geneva Convention.

In early February, he also discovered that the Federal Financial Control Service had added him to the “list of terrorists”. This Russian agency fights terrorist financing, but is used against political opponents. Meanwhile, Chebykin's team continues to collect the names of fallen Russian soldiers from the Omsk region as the government keeps this information hidden.

In Tbilisi, Stanislav Dmitrirovsky was working on a dossier for the International Criminal Court, which issued the arrest warrant against Putin. There he learned that the Russian state was preparing a new criminal case against him. His family was pressured to lure him to Russia, where he risks 20 years in prison. ‘But my wife has to look after her elderly father in Nizhny Novgorod’, he says. ‘I read so many books about Russian emigration after the 1917 revolution. Never did I think I would end up in such a situation myself.’ Still, Dmitryvsky continues to gather evidence of war crimes in Chechnya and Ukraine and prepare criminal cases for European courts.

European governments are also making trouble

After a lecture in Tbilisi, where he put signatures on the expired passports of Russian fans, Tichon Dzhadko recounts the odyssey that TV Rain went through. ‘The Georgian government did not want us to broadcast from Tbilisi. The border police even stopped one of our news anchors. Thanks to friends from Georgian TV stations, we were able to continue via YouTube. Then we got an invitation from Latvia, but six months later the Latvian media regulator revoked our licence again.’

‘After being “unwanted” in Russia and Georgia, we were now also a “threat to national security” in Latvia. One of our presenters had misspoken about supporting Russian soldiers in Ukraine. We fired him, but that was not enough for Latvia.’ Dzhadko is frustrated. ‘Those 139 million Russians in Russia will surely not disappear. Do European politicians consider it important to talk to them or not? We can do that as a Russian TV station. Or do you really want them to drift even further away from democratic values?’

Vladimir Romenskiy disagreed with his colleague's dismissal and started freelancing in recording rooms at Reforum Space Tbilisi, a Russian media hub. However, they too had to leave due to Georgia's law on foreign agents. Their backer, the Free Russia Foundation, is registered in the US. That is why we meet Romenskiy not in a studio, but in a café, preparing for a broadcast on Georgian demonstrations against election fraud.

The same thing happened to Emigration for Action. ‘We have to close this office because we receive donations from Russians worldwide’, says Zhukov. ‘Moreover, we are openly against the war and the Putin regime, which makes it even more risky. Helping Ukrainians is our priority. So we are now doing so without an official organisation and without a public statement against the war.’

Zhukov demonstrated for years against the law on foreign agents in Russia, and now he is affected by it again in exile. ‘The Georgian government is running after Putin’, he says. ‘Every year we have to renew our residence permits at the border, and every time there is uncertainty whether we will be allowed back in. One of our coordinators was not allowed to enter Georgia without explanation.’

Raïsa Frolova-Kozlova was present in Tbilisi at every demonstration against the Georgian law. ‘With us, that law was a decisive step towards dictatorship’, she says. ‘It led to the invasion of Ukraine and the assassination of an opposition leader.’ When she heard the news of Navalny's death, she felt the same shock as with the invasion of Ukraine. ‘The ground sank from under my feet, I had no country and no future.’

She put an invitation on the Instagram page of the book bar Auditoria: ‘Come cry, come drink vodka, come talk.’ Auditoria is a new place for knowledge and togetherness. ‘We sell books by banned Russian authors and organise events, but do not engage in a big political battle. We are just building a new home.’

© Map Design: Justine Corrijn / MO*

Cultural exodus

The exodus from Russia after the Ukraine invasion was also a cultural exodus, leading to new initiatives in the Caucasus. As Frolova-Kozlova opened Auditoria in Tbilisi, Grigori Karelski founded the book bar Common Ground in Yerevan. Lines of Russian and Armenian poetry are interwoven on the wall. Copies of the new Novaya Gazeta are flying out the door. In Russia, the newspaper is banned from printing, but here it is physically available again.

‘People see it as an artefact from the past’, says Karelski. ‘But Armenians are also interested. Common Ground does not only target Russians in Yerevan, but wants to promote connection between the two groups. In Tbilisi, such a place would be impossible. There is no communication between Georgians and Russians. Armenia is different.’

Communication between Georgians and Russians is exactly what the punk bar Secret Place in Tbilisi wants to encourage. And it does so through punk music. The bar itself really feels like a secret place. The entrance is tucked between two buildings and leads to an atmospheric courtyard, where founder Kirill has hung a banner reading ‘Stand With Ukraine’.

Another entrance takes you to a cramped basement. When the door opens, Kirill's punk band is on stage. ‘All dictators must die’ is written in large letters on the walls. Kirill and his friends have worked hard for three months to transform this downtown building into what it is today. ‘Secret Place is the only reason I'm still here’, Kirill says after the concert. ‘To be honest, I am a pessimist, but here we are creating an oasis in a world full of injustice. We are against war, against fascism, anywhere. We are also against the occupation of Palestine. With those values we unite everyone, Georgians, Russians, it doesn't matter.’

Kirill (right in the photo) is a well-known figure from the St. Petersburg punk scene. In Tbilisi he founded the anti-fascist punk bar Secret Place.

© Emiel Petrovitch

‘Don’t forget the Russians in Russia’

Is there a free Russia outside Russia? Many of our interlocutors do not believe so. We put the question to US researcher Aron Ouzilevski. In recent years, he conducted hundreds of interviews with active Russians who fled authoritarianism and militarism. He knows this historical exodus like no other.

‘I would like to say that the opposition in exile is a great human capital in which Europe should invest, but it does not function as one movement. Navalny's death had a big impact. There is a complete lack of leadership. When you spread an entire civil society across different countries, not only does exile weaken you, but it also divides you. The only Russian emigration wave that successfully returned to Russia to bring change was that of the Bolsheviks who initiated the Communist revolution. They were united behind one leader and one vision.’

So has Putin won?

The Navalny collaborators think not. Daniel Chebykin makes an impassioned speech about why he continues to make news for his own country in exile. ‘The hundreds of thousands of participants in Navalny's protest marches and all the people who laid flowers in the streets at his death have not disappeared. They are simply silent, out of fear. Navalny was the first opposition leader to make the idea of Russia as a normal country realistic. The man can die, but the idea cannot.’

Daniil Ken has proof that there are many of them. Navalny’s YouTube channels have a combined 6.5 million followers and reach 10 million unique viewers in Russia every month. ‘Our videos will not topple Putin, but they have caused problems in the recruitment of soldiers’, says Ken.

Vladimir Romenskiy also tries to uncover hidden facts about recruitment with his broadcasts for Echo of Moscow. ‘Recruitment happens mostly in disadvantaged regions. Thousands of people see war as their only way out. They are lured with high sums of money, but many die or return with PTSD, or end up in family violence and crime.’

Solidarity and freedom

TV Rain's Tichon Dzhadko sums it up in one word: solidarity. ‘The restrictive laws strengthen solidarity among Russians. It is punishable to support us, and we lost advertisers and donors in Russia. So we target viewers outside Russia for donations. This way they support our channel and the possibility for people in Russia to see real journalism. When they can watch an independent TV channel, they understand that they are not alone and that there is another, free Russia. We thus help build institutions for that other Russia, including in Russia itself. That way we don't have to start from scratch when the war is over, and this regime might be gone.’

At a hotel in Georgia, a Russian election observer living in exile in Lithuania gives an interview about the Georgian elections to a news anchor of Russian TV channel TV Rain broadcasting from the Netherlands. This October 2024 scene sums up the whole story: the internationalisation of free Russia.

This reportage was produced with the support of the Pascal Decroos Fund for Special Journalism.

This article was translated from Dutch by kompreno, which provides high-quality, distraction-free journalism in five languages. Partner of the European Press Prize, kompreno curates top stories from 30+ sources across 15 European countries. Join here to support independent journalism.

This article was translated from Dutch by kompreno, which provides high-quality, distraction-free journalism in five languages. Partner of the European Press Prize, kompreno curates top stories from 30+ sources across 15 European countries. Join here to support independent journalism.

The translation process is assisted by AI. The original article remains the definitive version. While we strive for top accuracy, some nuances of the original text may not be fully captured.

If you are proMO*...

Most of our work is published in Dutch, as a proMO* you will receive mainly Dutch content. That said we are constantly working to improve our translated work. You are always welcome to support us both as a proMO* or by supporting us with a donation. Want to know more? Contact us at promo@mo.be.

You help us grow and ensure that we can spread all our stories for free. You receive MO*Magazine and extra editions four times a year.

You are welcome at our events free of charge and have a chance to win free tickets for concerts, films, festivals and exhibitions.

You can enter into a dialogue with our journalists via a separate Facebook group.

Every month you receive a newsletter with a look behind the scenes.

You follow the authors and topics that interest you and you can keep the best articles for later.

Per month

€4,60

Pay monthly through domiciliation.

Meest gekozen

Per year

€60

Pay annually through domiciliation.

For a year

€65

Pay for one year.

Are you already proMO*

Then log in here