As long as living conditions in Africa do not improve, migration will not stop

Migration to Canary Islands puts immense pressure on Spain’s poorest region

© Michael Rhebergen

© Michael Rhebergen

By 2024, the Canary Islands were the favourite arrival point of West African migrants in the EU by a mile. But that puts immense pressure on Spain’s poorest region. That country sees great promise in Frontex and the EU Migration Pact. Whether these will deter young people in particular from venturing across remains an open question.

Every year, thousands of migrants leave Senegal via the deadliest migration route to the Canary Islands in search of a better life in Europe. Why exactly do African youths choose to risk their lives at sea? In a three-part series, MO* follows the migration route from West Africa to Europe in reverse. In part 1, we meet football coach Younousse who helps young Africans integrate.

This article was translated from Dutch by kompreno, which provides high-quality, distraction-free journalism in five languages. Partner of the European Press Prize, kompreno curates top stories from 30+ sources across 15 European countries. Join here to support independent journalism.

The ocean separating the Canary Islands from the African mainland is usually easy to see from the training complex of football club CD Tenerife. But today, a blanket of fine Sahara sand obscures the view.

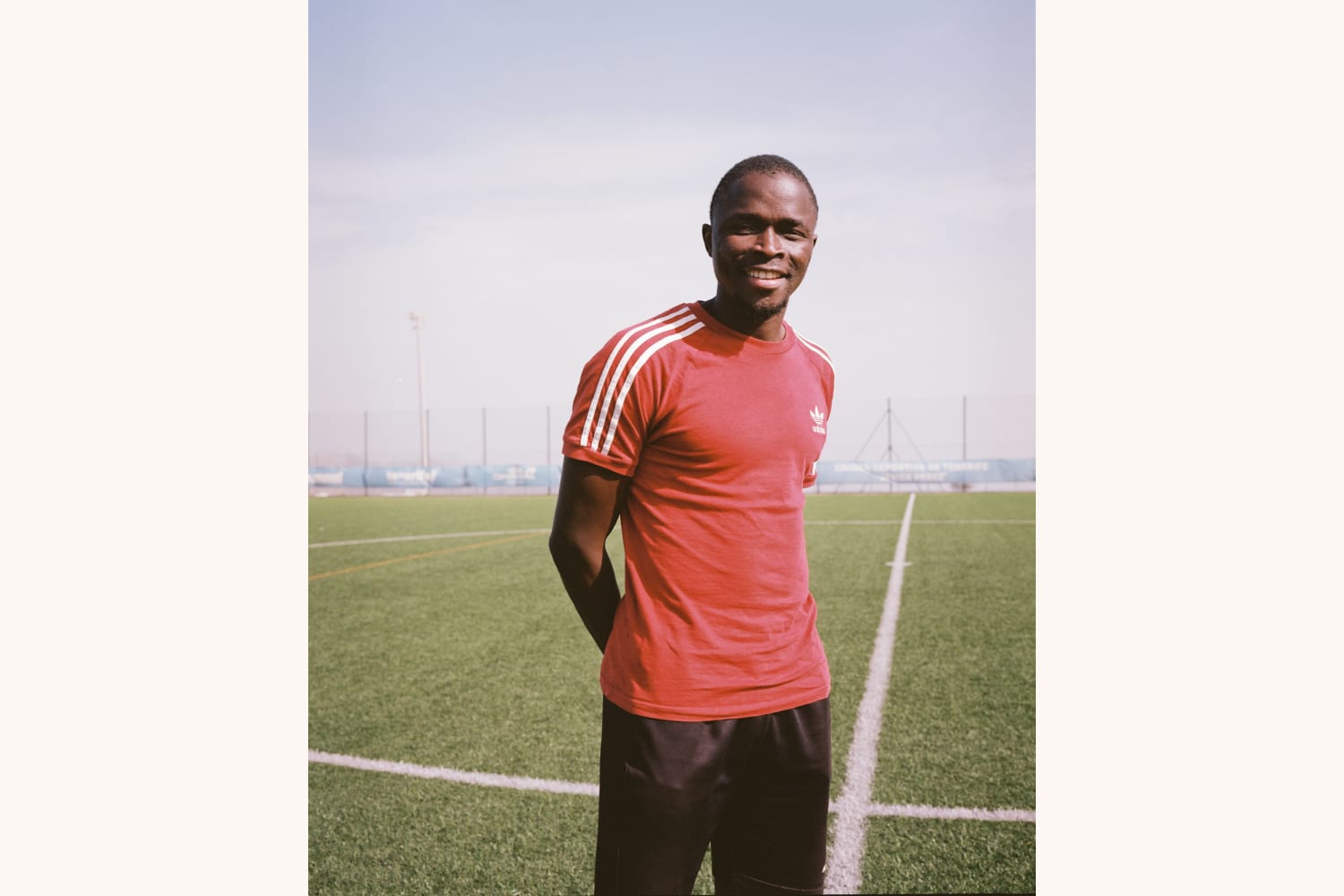

Youth coach Younousse Diop (31) grew up in the village of Gandiol in Senegal and has just given football training to a group of boys from Mali, Burkina Faso, Cameroon and Senegal. All left for Europe from the Senegalese coast and all floated around at sea for days until they were picked up by the Spanish coastguard.

From the lawn high up in the mountains, Younesse peers towards the ocean. Since 2021, he has been involved in a joint project between the local authorities, the Universidad de La Laguna of San Cristóbal and football club CD Tenerife to help young migrants integrate through sport.

Younesse knows what they went through. When he was 12, his own father put him on a boat bound for Spain to earn money. ‘In total, I spent 11 days on the open sea’, he says. ‘I fell asleep wet and woke up soaked. There were sharks and metres-high waves you couldn’t escape. Most of the boys here have also experienced that and are traumatised. The sea is hell.’

Many refugees from West Africa end up in Santa Cruz de Tenerife

© Michael Rhebergen

Deadliest migration route

Thousands of African migrants arrive in the Spanish Canary Islands every year. These are usually young men looking for work, but increasingly women and very young children are getting off the boats. According to recent figures from EU border agency Frontex, the sea route from Senegal to the archipelago will be the most active migration route to Europe by early 2025. A total of 7,200 people arrived in January and February.

The more than 1,000 kilometres across the open sea is also the world’s deadliest migration route, with 69 people drowning in late 2024 when a boat capsized off the Moroccan coast. In addition, migrants regularly get lost at sea and end up without food or drinking water. Boats carrying dead refugees from West Africa are found as far away as the South American coast.

According to Younesse, young people take these risks at face value to escape poverty in their countries. And that poverty is partly due to the EU itself, he argues. ‘European trawlers have been coming to steal fish from the sea off Senegal for years. Fishermen are surrounded by industrial fishing boats from abroad and our own politicians do absolutely nothing against it. Those at the top get a piece of the pie and the poor people at the bottom of society only get poorer. Young people realise this and are leaving for Europe because they want to make something of their lives.’

Five thousand underage migrants

The Canary Islands are the poorest region within the Spanish kingdom and just under a million people live in Tenerife. The never-ending flow of migrants therefore puts considerable pressure on the island.

A network of reception facilities provides temporary housing. But that costs the regional government about €156 million a year. The largest of these shelters is the Las Raíces tent camp, opened in 2020 with European funding, right next to Tenerife’s northern airport, where holidaymakers arrive in droves. Las Raíces is located on a former military site near the forest. More than two thousand underage asylum seekers live densely packed there.

‘Many have been victims of human trafficking, become addicted to drugs or suffer from mental health issues.’

In the car park near the camp, groups of boys hang around. Some of them have formed a running group and are running along the provincial road in bright orange vests. Three Moroccan boys have set up a barber shop between the cars and charge two euros per haircut. Further along, a Spanish family hands out bags of old clothes.

Sandra Rodríguez is Director-General for Youth for the regional government and, in that capacity, also responsible for conditions inside the camp. ‘There are currently around five thousand underage migrants trapped in Tenerife’, she says. ‘Many have been victims of human trafficking, became addicted or have mental health problems. When I started my work last year, almost no attention was paid to them.’

Minor refugees from Senegal.

© Michael Rhebergen

Lack of solidarity

In the Canary Islands, there are 2028 minors from Senegal, 1201 from Mali, 854 from Morocco, 612 from Gambia, 282 from Guinea and then some smaller numbers from countries such as Afghanistan and Bangladesh.

The main problem, according to Rodríguez, is that Spanish law requires regional governments to guarantee care and education for every child up to 16 years old. This causes major headaches in a poor region, where there are already too few places available in schools.

The lack of solidarity from mainland Spain stings her. Other regional administrators routinely block the amendment of the 1997 article of law that places responsibility over underage migrants with the arrival region. ‘I am angry and irritated about that’, Rodríguez fetes. ‘We have limited economic resources, personnel and housing here in the islands. When that law was made, no one could have foreseen the migration crisis we have today. We are an ultra-peripheral region and we have no direct access to the European Commission’s emergency funds. We are completely dependent on the Spanish state and it is precisely that state that does not recognise our problems.’

Frontex

The Spanish government representation office in the Canarian capital Santa Cruz is housed in a large building with heavy wooden interiors. On the wall hang carpets with the coat of arms of the Spanish crown and a large mural shows a colonial scene of conquerors from Spain coming to civilise the half-naked locals.

Representative Anselmo Pestana Padrón is a member of the Social Democratic Party (PSOE) and knows the problems on the islands. Yet within the EU, the Spanish government is pushing for a wider deployment of the European border agency Frontex to stem the flow of migration from Africa.

At a working lunch of European interior ministers in October 2024, Spain proposed that Frontex seek permission from governments in West Africa to stop migrant boats in their territorial waters.

‘We now have two helicopters that can share the location of refugee boats with African coastguards’, Padrón explained. ‘If Frontex itself can operate in the sea off Senegal then we will expand our capacity considerably. But on top of that, it is especially important to get circular migration right so that people can legally earn money within the EU and then return home safely. Now hundreds die at sea every year.’

He explains how that should work: ‘Migrants from Senegal are mostly economic migrants who may be deported again. Besides fishermen and farmers, they include people with university degrees. We need to better monitor exactly who comes ashore so that we can provide appropriate solutions. In many Spanish regions, for example, workers are needed in the hospitality or agriculture sectors. The guys who could get work there are now often stuck in the Canary Islands while unemployment is very high here.’

Start-up capital

Santa Cruz is Tenerife’s capital and is dozens of kilometres away from the tourist resorts with swimming pools on which the island’s economy floats. During the day, groups of men sit drinking beer and wine in small cafes in shabby suburbs. The riverbeds are so parched that a water crisis was declared in early 2024.

Cafeteria La Prince is located on the bottom floor of a brick residential complex opposite the largest migrant shelter in Santa Cruz. According to the manageress, Africans are exploited by a local bakery down the road. Next door to La Prince, five African boys rent a downstairs flat together.

The five beds in the flat are neatly made and hip trainers are displayed. On the wall hang the flags of Mali and Senegal. 19-year-old Moussa is from northern Mali and has found a job in a hotel after three years in the shelter.

His friend Sekou is the same age and grew up in the Malian capital Bamako. He has short dreadlocks, a large gold watch and he wears a Versace training jacket. Sekou works as an electrician and has completed several practical training courses in Spain.

‘When I have earned enough money, I want to return home to start my own electrician business and employ people’, he says. ‘That way I can help my country move forward. But salaries in Mali are very low and the bank won’t give you a loan. If you want to start a small business as a Malian, you really have to go to Europe first to raise start-up capital.’

You can’t control migration

According to Frontex, throughout 2024, the number of ‘irregular border crossings’ at Europe’s external border decreased by 38%. On the route from West Africa, that number actually increased by 18% to a record almost 47,000 arrivals, the highest number since Frontex started monitoring in 2009.

Migration is timeless and cannot be controlled. Certainly not as long as people in my home country struggle to make a living.

Much is expected in Brussels from the EU Migration Pact, which came into force in June 2024 and will be implemented in practice within two years. That new treaty should allow for better screening of exactly who is applying for asylum, faster return procedures have been agreed, and a solidarity scheme will be established that allows northern EU member states to financially support arrival countries in southern Europe or take over migrants. It will also make it easier for Frontex to work with African countries to stop migrant boats.

Yet Younesse Diop believes that all these initiatives will not stop migration until economic and living conditions in Africa improve. Merrily throwing balls over, he walks to the dressing room in the stadium. On social media, he shares football photos and on Instagram he shows pictures of his life in Spain.

He still speaks to his father in Gandiol regularly, Younesse says as he writes down his family’s contact details in Gandiol. But going back to Senegal is a bygone stage for the 30-something.

Younesse does a dance in the catacombs of the stadium and looks at the sea. ‘Tenerife is paradise for me. That’s because in this life, we Africans have to fight for our existence. This is my way and I try to help other migrant boys have their way. Migration is of all times and you cannot control it. Especially not while people in my homeland are struggling so hard to make a living.’

(Originally published in Dutch on may 5, 2025)

This series was made possible thanks to funding from the Pulitzer Centre. With the cooperation of Natalia González Vargas.

This article was translated from Dutch by kompreno, which provides high-quality, distraction-free journalism in five languages. Partner of the European Press Prize, kompreno curates top stories from 30+ sources across 15 European countries. Join here to support independent journalism.

This article was translated from Dutch by kompreno, which provides high-quality, distraction-free journalism in five languages. Partner of the European Press Prize, kompreno curates top stories from 30+ sources across 15 European countries. Join here to support independent journalism.

The translation is AI-assisted. The original article remains the final version. Despite our efforts to ensure accuracy, some nuances of the original text may not be fully reproduced.

If you are proMO*...

Most of our work is published in Dutch, as a proMO* you will receive mainly Dutch content. That said we are constantly working to improve our translated work. You are always welcome to support us both as a proMO* or by supporting us with a donation. Want to know more? Contact us at promo@mo.be.

You help us grow and ensure that we can spread all our stories for free. You receive MO*Magazine and extra editions four times a year.

You are welcome at our events free of charge and have a chance to win free tickets for concerts, films, festivals and exhibitions.

You can enter into a dialogue with our journalists via a separate Facebook group.

Every month you receive a newsletter with a look behind the scenes.

You follow the authors and topics that interest you and you can keep the best articles for later.

Per month

€4,60

Pay monthly through domiciliation.

Meest gekozen

Per year

€60

Pay annually through domiciliation.

For a year

€65

Pay for one year.

Are you already proMO*

Then log in here