‘Democracy is more than the will of the majority’

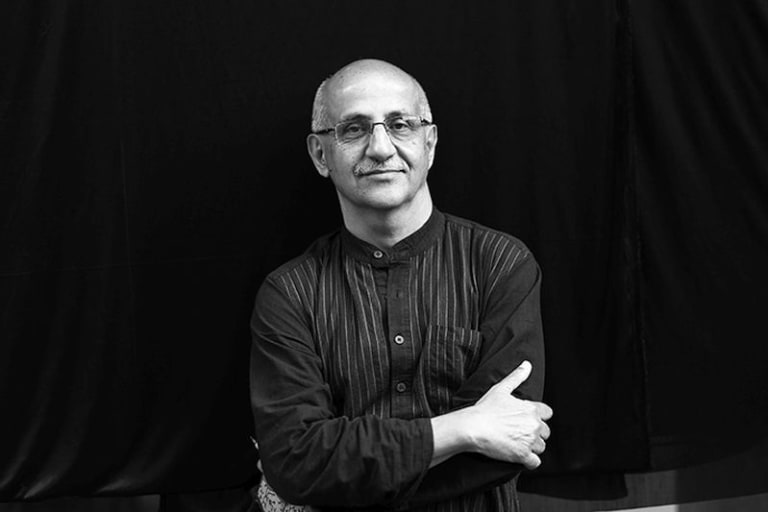

Harsh Mander: ‘Fighting hate with love, greed with brotherhood’

© Adnan Abidi / Reuters

© Adnan Abidi / Reuters

India is the world’s largest democracy, but is increasingly moving towards authoritarian rule under Prime Minister Modi. MO* spoke about this with one of India’s most respected activists, Harsh Mander. ‘It is the poor people who continue to defend democracy.’

With his bald head and small stature, Harsh Mander would be quite eligible to play the role of mahatma Gandhi, but really, it is time to film the life of Mander himself. As a four-year-old, he played on the lap of the newly fled and still in hiding Dalai Lama.

As a twenty-something, he toured India for four years in search of knowledge. He then spent 22 years as a district leader in all corners of India. His motto: ‘You are first the servant of the poorest and most vulnerable citizens, then of the constitution and finally of the elected government.’ He resigned in 2002 because, in his view, the murderous riots in Gujarat showed that the state did not defend its own constitution and left minorities to their own devices. This immediately marked a head-on clash with Gujarat’s then state prime minister Narendra Modi.

Between 2004 and 2014, he was part of a group of committed intellectuals who succeeded in legislating and passing laws on the right to information, food, education and employment. Mander launched innovative shelter initiatives for street children in public schools, set up clinics to serve homeless TB patients and founded a think tank to give the struggle for justice a better scientific basis. In 2017, he launched the Karwan-e-Mohabbat (the caravan of love) in response to rising violence against minorities, and in 2019, he supported with all his might the grassroots movement against a new citizenship law that threatened to discriminate against Muslims.

Over the past decade, we have witnessed our proud democracy rapidly deteriorate into authoritarian rule. This autocracy did not arrive in boots and uniforms; it was elected.Activist Harsh Mander

This set the stage for the national government, which has been under the control of the BJP and Narendra Modi since 2014. In recent years, all kinds of government agencies accused Mander of neglecting children in the shelters, using children for political purposes, laundering black money, financial malpractices and violating the law on receiving foreign funding. Nothing was proven, but complaints linger and funding for various initiatives dried up or became impossible. ‘The process is the punishment,’ Mander says of this.

India is ‘the world’s largest democracy’, I wrote last year, when 969 million citizens were allowed to cast their votes in national elections. Is that still true?

Harsh Mander: ‘India has always had a very vibrant democratic tradition. At independence, all citizens were immediately given the right to vote, even though the great mass of Indians were poor and with little or no literacy. Democracy in India did not just take shape through elections, there was also an independent judiciary and there were opinionated media.’

‘None of it was perfect, but democracy is not perfect anywhere in the world. Only in the last decade, we have seen our proud democracy rapidly deteriorate into authoritarian rule. This autocracy did not arrive in boots and uniforms, it was elected. That does not stop democracy from being lost. The ruling party takes over the institutions of the state, there is a climate of fear and intimidation, both the judiciary and the media have lost their independence, and currently even the credibility of the electoral system is threatened. And above all, minorities are treated as second-class citizens. Especially the Muslims, even though there are over 200 million of them in India.’

How would you define democracy?

Harsh Mander: ‘A democracy can never be defined only as "the will of the majority". Democracy needs at least as much "equal rights and protection for vulnerable minorities". The experience of the Third Reich in Germany proves that the latter is even more essential than the former.’

‘The four pillars of the Indian constitution are justice, freedom, equality and fraternity. Presenting the final version of the constitution, the lead author, Dr Ambedkar, noted that justice, freedom and equality are possible without fraternity, but then they depend entirely on the will and actions of the state. Fraternity, in other words, is the central foundation of democracy. The rule of law is the instrument, but the foundations of democracy go much deeper.’

How important are rights?

Harsh Mander: ‘Rights are hugely important, but they are not a recent discovery or construction to address injustice in the world. Nor are human rights a Western invention or a European value, nor a mere tool of conflict management. Rights as we formulate them today are built on a much older foundation of empathy and solidarity.’

Prime Minister Modi’s BJP does not advocate fraternity or empathy, but the power of the majority. And in doing so, it garners far more votes than any other party.

Harsh Mander: ‘You see this reality emerging in a lot of places around the world. The world seems beholden to leaders who intimidate vulnerable minorities, who preach hate rather than connection, who behave rudely and brutally and are spectacularly insensitive to the suffering of victims. It is a crisis of civilisation that we only halfway understand.’

‘In India, this evolution is perhaps even more dangerous than in many Western countries because it is not just a matter of anti-establishment rebellion and gut feelings. The power of Modi and the BJP is vested in a distinct ideological and paramilitary mass movement that celebrates its centenary this year. That Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh is the largest voluntary organisation in the world. Certainly in its early years, it admired fascism and Nazism, and it advocates second-class citizenship for minorities. Resistance to authoritarianism in India, therefore, cannot suffice with an electoral strategy against Modi and his government.’

‘Most disturbing is the massive silence that prevails in India today. Everyone is trying to stay under the radar. Even the political opposition is largely silent about what is being done to the Muslim minority. The media is silent on what really matters and makes incredible noise about everything else. There are individuals in civil society, the alternative media and the judiciary who are willing to stick their necks out, but they have become the exceptions. This is not surprising, because anyone who goes against the BJP risks being accused of all kinds of crimes, from financial rigging to terrorism or treason.’

‘The resistance of farmers in 2020–2021 was incredibly strong. They understood how dangerous it was to put agriculture in the hands of oligarchs and commercial consortia.’

© Harsh Mander

When democracy has to give way to growing authoritarianism, you also expect resistance. Where does that take place and who are its instigators?

Harsh Mander: ‘In the West, voters for the far-right tend to be less educated and socio-economically vulnerable. In India, it is just the opposite. The richer and better educated, the more they are part of the political or economic elite, the more likely people are to choose the BJP. It is at the bottom of the social ladder, among farmers and workers, that the idea of India as a land of equal opportunities and equal rights is still most vivid. They hold the country together.’

You mention farmers in particular.

Harsh Mander: ‘Their resistance in 2020 - 2021 was incredibly strong. They understood how dangerous it was to put agriculture in the hands of oligarchs and commercial syndicates. The fact that they stayed camped on the borders of Delhi for more than a year was impressive. And also the way they conducted and articulated their resistance was particularly powerful because it was built on creativity, on joy, on mutual support. Their resistance gave shape to what fraternity means.’

‘The other resistance movement that stands out head and shoulders above the rest is the one against the Citizens Amendment Act (CAA, the citizenship law that gives refugees from neighbouring countries accelerated access to Indian citizenship, except if the refugees are Muslim, ed.). Perhaps those 100 days of resistance in late 2019, early 2020 were the most wonderful period in India’s independent history.’

‘What made that grassroots movement so special was that the constitution was elevated as the central symbol of resistance to the government. The CAA was clearly directed against Muslims, but the movement was co-created by Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and other minorities. This is very important, because otherwise Muslims are left alone to defend their own rights and the secular republic.’

‘The resistance to the CAA was initiated and led by Muslim women from working-class neighbourhoods. This confirmed what I already learnt during my years in district administrations across India, namely that men have a hard time dealing with situations where everything seems to be falling apart. It also convinced me that times of crisis like we are experiencing today need women leaders. Without women, we are stuck in the violent now.’

Your own 2017 initiative, the Karwan-e-Mohabbat or Caravan of Love, also focused on human tenderness rather than harsh political resistance. Why?

Harsh Mander: ‘How do you organise resistance to hate? By hating the other? That only leaves more and harsher hatred, Mahatma Gandhi taught us. The mere nervousness and discomfort with which the government responds to the Karwan-e-Mohabbat shows that warm fraternity is an effective form of resistance.’

‘The Karwan visits the relatives of people who were lynched or victims of a hate crime. They are not human rights delegations, but condolence visits in which we share in the suffering and grief of bereaved families. We ask forgiveness for what society has done to them and for what we have become as a society. We commit to staying by their side as they seek justice and try to rebuild their lives. And finally, we tell a story.’

‘The caravan was conceived in 2017 as a one-off initiative, but in the meantime the hatred persisted and the killings continued. Moreover, these visits really turned out to mean so much to the bereaved families that we have since completed more than 50 caravan tours.’

Hindu nationalism became the dominant political ideology during the period when neoliberalism became the dominant economic ideology. Is this simultaneity a coincidence?

Harsh Mander: ‘Authoritarian governance is characterised by hostility to minorities, brutal public discourse, impatience towards democratic procedures and the absence of compassion for victims. As a fifth characteristic you can add: the very close links with big business. An economy of oligarchs and a fascist majority government arrive hand in hand.’

‘Neoliberal morality replaced fraternity with greed. Everyone had to think of their own gain from now on and, as a result, a better world for all would naturally emerge. Meanwhile, it is clear that not enough jobs are being created, even though enormous wealth has been created. And if you look at real decent work, it even went backwards. That means the vast majority of young people in India have no future to look forward to. As an alternative, politics offers a project that turns minorities and migrants into scapegoats.’

Meanwhile, you remain radically committed to the rights of the Muslim minority. This is striking because your family was forcibly expelled from Pakistan in 1947.

Harsh Mander: ‘My parents’ village was one of the places in Punjab worst affected by violence by Muslims against Sikhs. Consequently, much of my extended family is ashamed of me and my views. My response to this is: who better to understand the misery of people persecuted and targeted because of their religion and identity than those of us who have experienced it ourselves? By the way, I would also like to ask that question to Israel’s Zionists. How can people who experienced the worst during the Holocaust now in turn approve cruel and violent policies against others?’

Read also

This article was translated from Dutch by the author, Gie Goris